Friction: Thirty‑Six Frames Against the Feed

Film taught me to work slowly, accept imperfection, and keep most photographs “for myself” rather than for an algorithmic audience. In a culture that rewards constant output; manual focus, thirty‑six frames, and images that may never hit a feed feel almost radical.

Between the ages of 10 and 15, I drifted through piano recitals, competitive tennis, and swimming before finding a first real obsession in DJing and record collecting. When I moved to Dubai in 2018, that obsession faded; the hassle of transporting records to the UAE, and the lack of a record‑store community, slowly killed a hobby that had defined much of my early teens. Around that time, my step‑dad handed me his retro‑futuristic Canon AE‑1, a janky, finicky little thing, along with a ragged plastic bag of very expired film stock. I became attached to this “ancient” camera almost immediately.

Until then, I had never seriously considered photography or the visual arts; those interests always seemed to belong to my sister, who drew and painted far better than I ever could. Cameras were mostly for travel snapshots or the occasional nice sunset on my phone, which felt good enough. Shooting 35mm, though, felt meditative. Like DJing and record collecting, working with film is a physical, involved process where you handle each step with care. Even as I fell deep into film photography, I did not feel any urgency to study it; for a long time, it was simply something I did for myself.

Most of 2023 and 2024 were spent shooting only film, partly because a new digital body was financially out of reach and partly because the limitations felt right. Working with 35mm gives you just 36 exposures, so you try to make every one count, yet caution and precision never guarantee a good photograph. I like to leave a long gap between making pictures and looking at them; distance lets me see the work more generously. Many of my favourite images only revealed themselves after months, while some frames I almost discarded ended up resonating with others. Starting with film taught me that maybe one in ten frames will truly matter, and that art and perception are deeply subjective—you are often your own harshest critic.

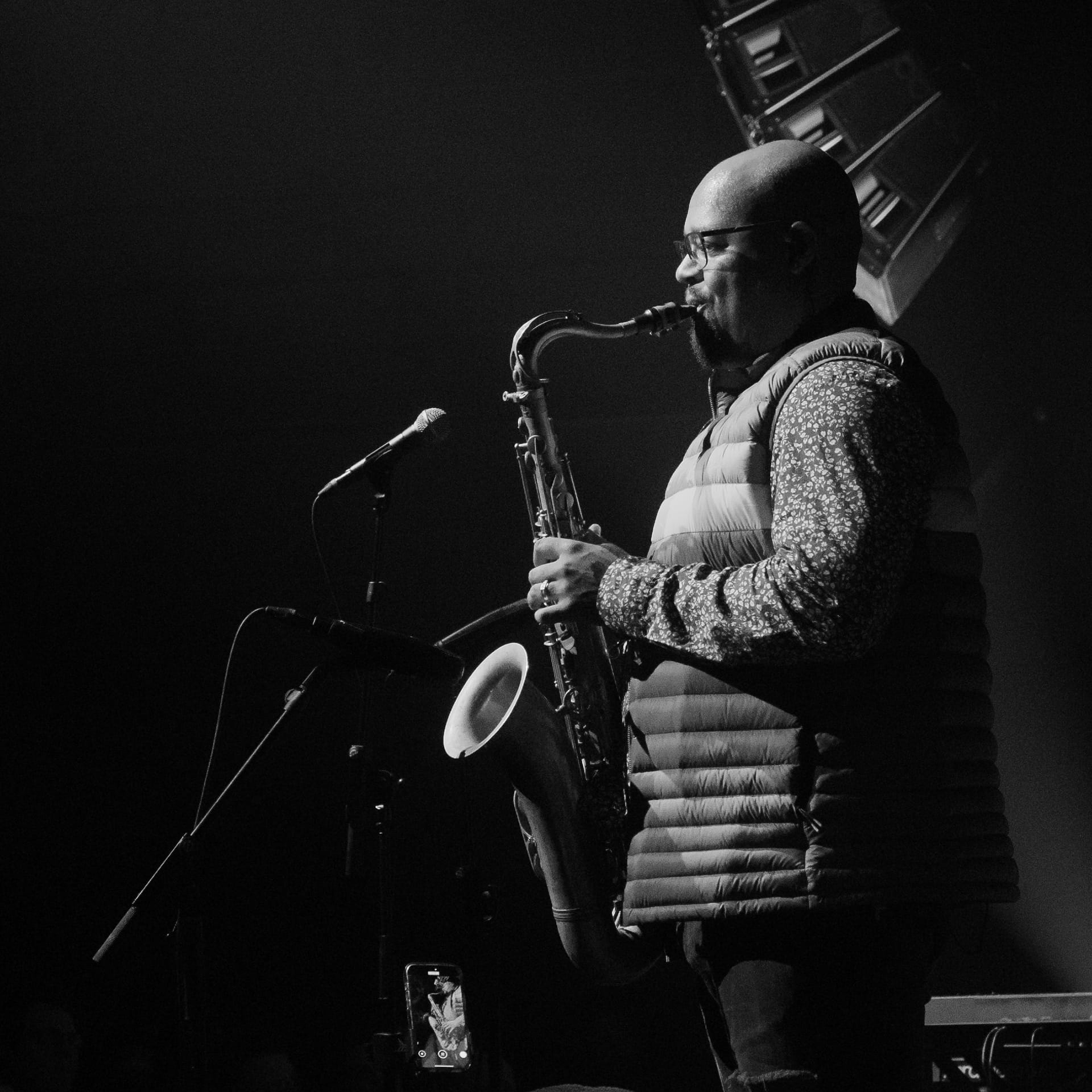

Going digital in 2022–2023 raised a different set of questions about how I wanted to make images. Manual adjustments—focus, aperture, shutter speed—had become intuitive. I bought a used Fujifilm X‑T10 as a way into digital, pairing it with my AE‑1 for concert photography, and in 2024 I picked up my first “serious” digital camera, the Ricoh GR IIIx. On paper, these cameras are optically impressive and highly capable, but in practice it often felt as if I had to fight them to make my shots feel intentional. I hoped the Fujifilm X100VI, with its film simulations and rangefinder‑style viewfinder, would bring me closer to a film‑like way of working—just without the cost per frame.

Across all of these digital bodies, it felt like I was wrestling the camera into doing what I wanted. I seem to be in a small minority of people who genuinely enjoys manual focusing and exposure, chasing that feeling of getting a shot “just right.” The usual selling points of digital—autofocus, automatic exposure, speed, portability—became friction in my process rather than conveniences. Digital photography is often tied to a “run‑and‑gun” mentality, where the goal is to move quickly and get technically good images without thinking too much. Even when manual focus is technically available, focus‑by‑wire and electronic focusing often feel imprecise and disconnected compared to a mechanical manual‑focus lens.

I do not believe that doing things the hard way is automatically better. But shooting film—with its ISO limits, manual focus, and reliance on the film stock and development—reminds me that constraints and uncertainty are an essential part of how I like to photograph. I am more interested in committing to decisions early in the process and accepting the imperfections that follow. In a culture where every hobby risks becoming a side hustle, choosing to work slowly and imperfectly starts to feel almost radical. That slowness, and the willingness to risk “wasted” frames, is a big part of why I keep photographing at all. Over time, I have even developed a kind of affection for the mess‑ups—the over‑ and under‑exposed frames, the not‑quite‑sharp pictures that would never make it past the cutting‑room floor, but still feel honest to my flaws and the way I see.

Getting more serious about photography in recent years has also meant getting pulled into YouTube videos and online threads about every possible niche. Topics that previously were not concerns became the only things I cared about. This obsession has only worsened as many creators have shifted to short‑form content and hyper‑optimised “grow your photography” advice, while platforms that still focus on teaching and long‑form reflection feel like rare exceptions to the modern convention. Conversations about film versus digital, JPEG versus RAW, or Camera A versus Camera B are everywhere, and the most egregious for me personally was the endless “this is the best camera for X price!” content. I often found myself more anxious about not being in the “right” camera system, or worrying that my photo reportages were not “good enough,” or chasing the latest body that promised to feel more like film, which is how I ended up with the Fujifilm X100VI in the first place. This is not to claim that the online photography space does not have good content—in many cases, it is how I have learned the more practical tools and tricks for my photography. The caveat is that constantly following these creators can very quickly lead to a rabbit hole of FOMO: inspiration can become impostor syndrome, and you learn not to shoot, but to obsess over what is and what might make your photography “good.”

All of this sits inside a bigger shift: most photographs now begin and end on social media. The personal photograph that might once have been printed, put in an album, and revisited years later is now just as likely to be a temporary message, a story bubble, or a tile in an infinite grid. The meaning of a picture is less about what it will evoke in ten years and more about what it does in the next ten minutes—does it get a reaction, convey a mood, keep you present in other people’s feeds. Cartier‑Bresson once described books and exhibitions as almost permanent forms of showing photographs, set against the fading snapshot in a wallet and the glossy advertising catalogue; he refused to define photography for everyone, only for himself. That distinction feels even sharper now, when so many images vanish into feeds and archives almost as soon as they appear. I wonder how Henri would react in the advent of social media today.

Photography has become part of an ongoing conversation, a visual vernacular of meals, outfits, and views, where the photograph is a unit of communication rather than a long‑term object. For photographers, this creates a confusing landscape of incentives. The platforms that give the widest exposure also reward frequency over depth, consistency over doubt, and clean, easily legible images over awkward, ambiguous ones. It becomes much easier to measure likes, shares, and follower counts than to measure whether a photograph changed how you see a place, helped you hang onto a fleeting feeling, or brought you closer to someone you care about. When pictures are treated as a currency for attention, it can be hard to remember that they are also records of life, attempts to understand the world, or quiet gifts to a future self, which gets at many of my issues with how social media currently works. In many cases, the way photographs are used online feels disingenuous: less about making or seeing, and more about maintaining a constant, optimized presence.

Some people photograph to build an audience, find clients, or sell prints, and social media can be an incredibly powerful tool for that. Others photograph to document family, to prove they were somewhere, to remember. Some photograph to slow down and pay attention, to notice light on a wall or the way someone’s hands move when they talk. There is a whole tradition of photographers and writers who see photography as a way of affirming meaning, of keeping an affection for life intact in the face of boredom or despair. None of these reasons is more “correct” than the others, but they do not all survive equally well under the same algorithmic pressures.

In that context, the questions people ask when photography comes up—“Why have you not made any money from this?”, “Have you tried getting people to pay you?”—start to feel strangely narrow. Many people who describe themselves as photographers seem primarily motivated by money or clout: the goal is not just to make photographs, but to turn oneself into a brand. You are no longer just a person who photographs; you are a product whose images are judged less on what they reveal than on what they return in views, bookings, or sponsorships. Those questions assume the point is optimisation and income: are you leveraging this skill, extracting value, turning it into content or a brand.

What feels more urgent, at least to me, are different questions. What does it mean to keep a practice “for yourself” when every photograph can be uploaded, judged, and monetised in seconds. What changes when your primary audience shifts from your future self and a handful of friends to an invisible crowd and an opaque recommendation system. How much of the way we photograph now is shaped by what the feed rewards, and how much is still ours—our preferences, our pace, our willingness to make pictures that might never leave a hard drive or a shoebox of prints.

Film, for me, is one way of protecting a different answer to those questions. Thirty‑six exposures, a manual focus ring, and the long delay between pressing the shutter and seeing the image again create a rhythm that does not map neatly onto the logic of the feed. That rhythm does not make the work better or more authentic by itself, but it reminds me that photography can be a conversation with the world rather than a performance for it. Somewhere between the run‑and‑gun mentality of digital convenience and the deliberate drag of film is the space where many of us are trying to figure out what photography is for, and who, exactly, we are making these pictures for in the first place.

As someone who has only recently started to think of themself as a photographer, talking about these questions can feel difficult and exposed. Calling yourself a photographer comes with built‑in expectations and a series of existential questions about why you make images at all, what and who they are “for,” and whether they are worth anything beyond likes or invoices. In recent years, those questions have only sharpened as artificial intelligence has become a central topic in conversations about art and photography, with more and more people asking what it means to keep making photographs in a world where images can be generated instantly and endlessly. Questions like “Are you getting paid?” or comments such as “At least you are getting exposure and credit” largely miss the point of why this practice began for me in the first place.

I take a lot from Henri Cartier‑Bresson’s way of thinking about photography: that each of us has to define it for ourself, rather than chasing a single universal purpose or standard. In that sense, my own definition is modest. Photography is, for me, a way of paying attention, of staying in conversation with the world, and of leaving behind a trail of imperfect, personal images that do not need to justify themselves as content, products, or prompts for a machine. It is a way to connect with the people around me, with society, and with the wider world.